The Serrated Bread Knife

- May 14, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: May 4, 2023

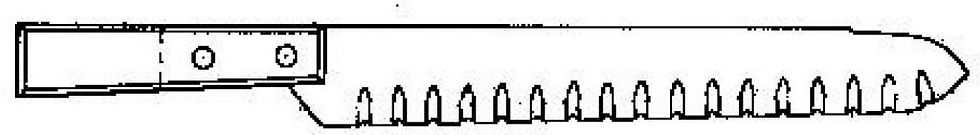

Figure 1. Christy’s 1889 patent drawing for tang-less knives. Christy described the bottom knife as a “bread knife,” which was the first time a knife with a serrated blade was referred to by that name.

by Bob Roger Reprinted from The Chronicle, Volume 63, No. 1, March 2010

First, there was bread. Then, a long time later in Fremont, Ohio, the serrated bread knife — an interesting tool that is both very functional and pleasing to look at — arrived.

Bread can be cut with almost any sharp knife, but a serrated blade performs exceptionally well, and knives with six- to ten-inch serrated blades are usually known as bread knives. The shorter versions are also used for cake, tomatoes, and other foods that are tough on the outside and soft on the inside. This article will examine serrated bread knife patents issued before 1940 in the United States.

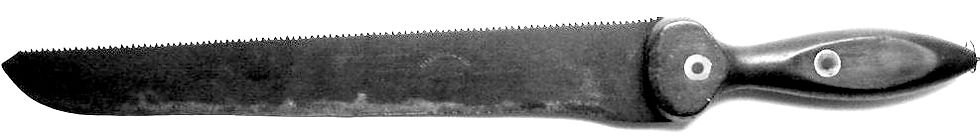

Figure 2. Christy’s 1891 patent drawing for a serrated blade knife.

The American table cutlery industry began in 1834, and by 1919 there were more than sixty American kitchen, butcher, and industrial knife makers. (1) The typical knife used for bread, cake, tomatoes, and similar foods was a sharp, thin-bladed slicing knife with a straight, smooth edge — a style that was well-represented in the products of this industry. But the industry was more than fifty years old by the time the serrated-blade bread knife was invented, which is especially interesting as the use of saw blades for meat and bone cutting had been established long before.

Figure 3. An example of a Christy’s bread knife marked with the 1889 and 1891 dates.

Russ J. Christy founded the Christy Knife Company in Fremont, Ohio, about 1890, and he should be considered the father of the serrated bread knife. Figure 1 shows the drawing for patent no. 414,973, issued on November 12, 1889, to Christy. This patent was for his wire-handled, tang-less knives. In the patent drawing, he showed two different ways of fastening the handle to the blade, and in the description he referred to the bottom knife with the serrated blade in the drawing as a “bread knife.” He explained the difference between his serrated blade and a saw blade by noting that the serrations were thinner than the upper blade and had no set in them. He also explained that the serrations are sharp at their bottoms as well as at their tops. He did not, however, claim the serrated blade in this patent.

Christy’s next patent, no. 460,677, was issued on October 6, 1891, and assigned to Robert H. Rice of Fremont and Leonidas H. Cress of New York City. This patent for a tang-less serrated blade had the serrations ground on one side only and were formed by reverse curves, so that the space between the teeth was of similar curve to the teeth (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows an example of Christy’s bread knife marked with the 1889 and 1891 patent dates. Christy introduced these in 1892. (2)

Christy had been residing in Sandusky when he submitted his applications for these two patents (no. 460,677 was submitted on November 4, 1890). By the time he submitted his third patent (April, 1895), he had moved to Fremont.

Figure 4. Eberhard’s handle.

The next patent related to serrated bread knives was no. 485,264 issued on November 1, 1892, to John J. Eberhard of Fremont for an iron knife handle (Figure 4). He assigned it to the Clauss Shear Company, also of Fremont. John H. Clauss, who had founded the company in 1878, introduced his scalloped-edge, tang-less bread knives with the Eberhard iron handle beginning in 1892. Figure 5 shows one of Clauss’s knives, which is marked “CLAUSS and FREMONT,” with the Eberhard patent handle. Note that Clauss’s blade serrations are alternately large and small, and that there is not much of a reverse curve between them.

Figure 5. Clauss’s bread knife with Eberhard’s handle.

Kenneth Cope in Kitchen Collectibles illustrates two bread knives made by Charles F. Spery & Company of St. Louis, Missouri. (3) They are both marked “SPERY” and appear to have Christy’s blade. The first was offered in 1894 and has a decorative handle quite similar to Eberhard’s patent. In 1895, the firm offered the second bread knife as part of a set, and all of the items in the set clearly have Christy’s handle. The Spery company was probably absorbed by Illinois Cutlery in 1898, which continued to offer nearly identical products.

Figure 6. Ward’s 1894-95 “Christy-style” knife.

A bread and cake knife with diagonal corrugations across the entire blade, called Ball’s Bread & Cake Knife, was introduced in 1894. (4) It had a metal loop handle, somewhat like Christy’s, and was made by the Aluminum Novelty Company of Canton, Ohio. Also in 1894, the American Cutlery Company introduced a bread knife like Christy’s called the American Bread Knife. (5) The 1894-95 Montgomery Ward & Co. catalogue illustrated a set of serrated knives — bread, cake, and paring. (6) Even though Montgomery Ward refers to them as “Christy-style” knives, the handles are shaped somewhat differently from Christy’s handles and are fastened to the blades more in the manner of Ball’s knife that had been made by Aluminum Novelty. Also, there were no reverse curves between the serrations as on the Christy blades. Ward’s bread knife is shown in Figure 6, and its markings indicate it was made by Abbott Machine Co. of Chicago.

Figure 7. Hayes & Lewis’s patent.

The first patent for a serrated bread knife with a tang and wooden handle appears to be no. 495,110, issued April 11, 1893, to Francis Hayes and Fred J. Lewis, both of London, Ontario. They assigned one-third interest in the patent to William S. B. Barkwell, also of London. Their blade has serrations separated by sections of a normal straight blade, and it is serrated and sharpened on one side only (Figure 7). Clark & Parsons of East Wilton, Maine, in 1910 made a Lightning nine-inch bread knife that appears to use Hayes’s patent blade. (7)

Figure 8. Christy’s 1895 patent.

Figures 9 a (above) & b (below). A Keen Kutter knife of Christy’s design and detail.

Christy’s third patent, no. D24,386, was issued on June 11, 1895 (Figure 8). It had his serrated blade sharpened on one side and a tang in a wooden handle with an ornamental ferrule. Christy introduced it in 1895 as the model no. 16, and many companies sold knives with this design, including E. C. Simmons’s bread knife marked “KEEN KUTTER” shown in Figures 9a and b. (8) The 1902 Sears catalog illustrates five serrated-edge bread knives, all with Christy’s patented blade (Figure 10). (9) One of the knives is marked “AMERICAN CUTLERY CO’S CELEBRATED VICTOR BRAND.” The middle knife is Christy’s 1895 design patent marked “VICTOR,” and the bottom knife is Christy’s 1891 patent labeled “CHRISTY BREAD KNIFE.” It is also described as the “Christy Pattern and Genuine Christy Knife” in the catalog.

Figure 10. Sears serrated bread knives, 1902. The second knife from the top is marked “AMERICAN CUTLERY CO’S CELEBRATED VICTOR BRAND.” The middle knife is Christy’s 1895 design patent marked “VICTOR,” and the second knife from the bottom has a saw back for cutting bones. The bottom knife is Christy’s 1891 patent.

The second knife from the bottom in Figure 10 has a saw back for cutting bones. It is also marked VICTOR, and its label reads “Saw Back Ham Slicer with serrated edge, 8 inches long.” Will slice bread hot or cold. The best thing on earth for cutting frosted cake. Cuts meat or bone.” There is a similar saw-back, serrated knife marked “ARIOSA COFFEE” (Figure 11). The patented Ariosa coffee brand was made by John and Charles Arbuckle of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, beginning in 1865. It is named for Ariosa, Pennsylvania, a locality in Adams County near Gettysburg. It is so similar to the Victor that it was probably also made by American Cutlery Company, which went out of business circa 1917.

Figure 11a (above) and b (below). A saw-back serrated bread knife and a detail of the blade.

The saw-back idea had arisen much earlier in the form of a butcher knife. Smith’s 1858 patent (no. 21,520) combined a spring scale in the handle of a saw-back butcher’s knife (Figure 12). The wording in the patent implies that butcher’s saw knives were in common use at that time. In a letter to The Chronicle, EAIA member Frank Kosmerl notes that he had found “W. Stillman’s patented Saw Knives” listed for sale in an 1838 catalog from the William H. Carr & Co. of Philadelphia. (10) William Stillman had received at least three patents between 1801 and 1818 for machinery for cutting veneer and cloth, and he may have had others. Most of the early patents were lost in a fire in December 1836, and a patent by Stillman for a saw-knife could have been among them. Butcher’s saw knives were also made by Henry and Charles Disston’s Butcher Saw and Trowel Department between 1865 and 1895 (Figures 13). Obviously, the idea of adding a bone saw on the back of a knife had been in practice before it was used on bread knives.

Figure 12. Smith’s patent scale on a saw knife.

On June 18, 1912, Leonidas H. Cress of West Newton, Massachusetts, was issued patent no. D42,619 for a serrated knife ornamental design with serrations like Christy’s patent. Christy had assigned half of his 1891 patent to Cress, so there was no infringement. Cress assigned his design patent to the Federal Tool Company of Everett, Massachusetts, and Cope illustrates the knife as a bread knife and ham slicer made by Federal. Cress’s patent is shown in Figure 14. (11)

Figure 13 a (above) & b (below). “Disston & Bro” saw knife and detail.

Frederick Lehrmann of Turtle Creek, Pennsylvania, was issued design patent no. D48,474 on January 18, 1916, for another form of serrated knife, which he called a combination culinary tool (Figure 15). It appears to have been too short for a bread knife, but there are no details in the patent to verify this. On July 4, 1916, Samuel Bowman was issued design patent no. D49,295 for a bread and cake knife with a serrated blade (Figure 16). The serrations appear to be small saw teeth. The last serrated-blade patent prior to 1940 is no. 2,059,414 issued on November 3, 1936, to William P. Taylor of Colorado Springs, Colorado, for his crumb-less bread knife (Figure 17). While Taylor’s knife appears similar to the Hayes and Lewis patent shown in Figure 7, Taylor’s blade has the serrations cut into both sides of the blade, and it is sharpened (that is, beveled) on both sides, whereas Hayes and Lewis’s blade is one-sided.

Figure 14. Cress’s ornamental design patent.

Figure 15. Lehrmann’s knife.

Figure 16. Bowman’s bread knife.

Figure 17. Taylor’s bread knife.

Notes 1. Bernard Levine, Levine’s Guide to Knives, 4th Edition (Iola, Wisconsin: DBI Books, 1997). 2. Kenneth L. Cope, Kitchen Collectibles (Mendham, N.J.: The Astragal Press, 2000). 3. Cope. 4. Cope. 5. Cope. 6. Montgomery Ward & Co. Fall & Winter 1894-95 Catalogue, Follett Publishing Co., reproduced in 1970 by The Gun Digest Co. 7. Cope. 8. Cope. 9. The Sears, Roebuck and Co. Catalogue of 1902, reproduced in 1969 by Crown Publishers, Inc. 10. Letter on Saw-Knives, Frank Kosmerl, The Chronicle 48, no. 1 (1995):19. 11. Cope.

Author Bob Roger is a frequent contributor to The Chronicle. Most recently, he wrote a series of articles on “Patented Hand-Held, Ice-Reducing Tools,” which appeared in The Chronicle 60, nos. 3 and 4 and 61, no. 1.

Comments